Source_Code

Source_Code

Our Project

Generative Adversarial Networks

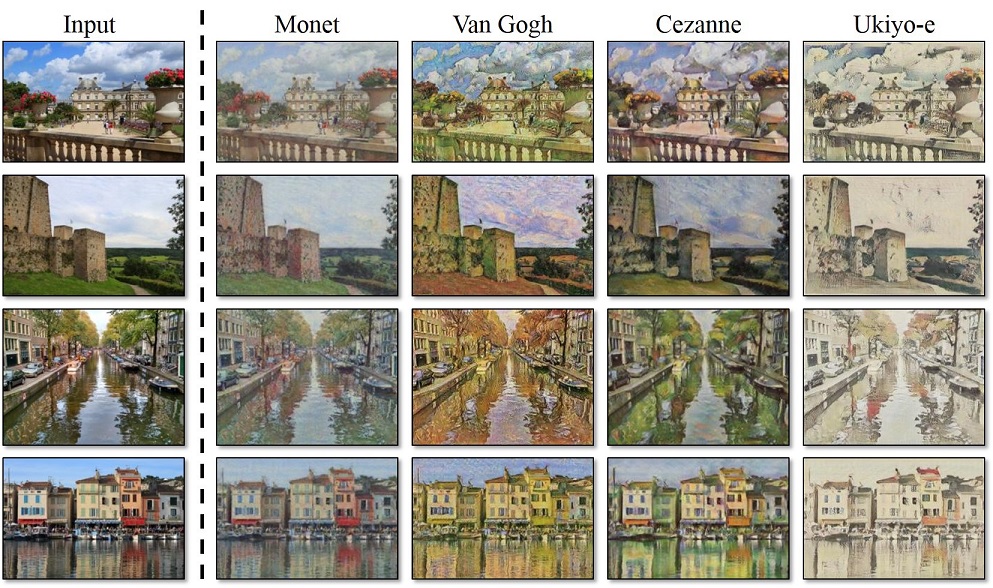

Generative adversarial networks (GANs), which were first introduced by Goodfellow, et al. in 2014, are an unsupervised learning technique, capable of producing entirely new data, based on features that were learned during the model training. One popular use case of this technique are so called Deepfakes, where a person’s face is swapped with someone else’s in a video. GANs can also be used for style transfer. An example of this is turning a photograph into a painting, that looks like it was made by a famous artist such as Van Gogh or Monet using a process called pixel-to-pixel translation.

GANs consist of two neural networks: The generator generates new data instances and the discriminator must decide whether a given instance belongs to a real dataset or has been created by the generator. They are competing against each other during the training, where the generator is trying to fool the discriminator into thinking its generated data instances are real. The discriminator meanwhile is trying to get as good at telling the fake data from the real one as possible. In each training iteration the generator and discriminator are trained separately. A loss function gives them feedback how close or far they are from their goal. Then their weights in the network, which are used to calculate their output, are adjusted respectively. This cycle continues until the generator is able to create plausible enough data so that the discriminator cannot properly distinguish between real and fake anymore.

Our approach is based on a paper that uses GANs for 2D pathfinding. Both the paper and the previous style transfer example use a specific version of GANs for this, a so-called conditional GAN. In a classic GAN the generator generates data from random noise with less control over the output.

A conditional GAN instead receives extra input. This could be a photo or in case of the paper a 2D world. This world contains a start and goal marker for pathfinding. The network then learns to generate a 2D world with a result path drawn in, that connects start and goal (pixel-to-pixel translation). The figure below demonstrates this concept. On the left the model prediction input is shown.The black pixels represent start and goal. The gray pixels are obstacles in the world that need to be navigated around. In the middle is the ground truth as comparison. The output from the trained network is on the right. It managed to predict a path that is close to the ground truth, but has a gap and took a slightly different path near the goal on the top right. The GAN basically learns to imitate the algorithm that was used for creating the paths in the ground-truth images (here A*).

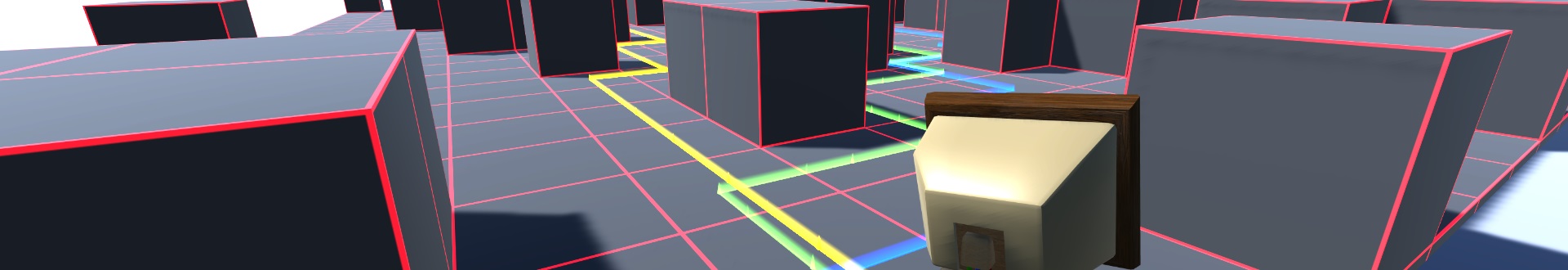

In our project we advanced this approach to learn a voxel-to-voxel translation so we can represent three dimensional worlds. With our technique we can predict paths for combinations of unknown worlds and different starts and goals, as long as we have a model for the target world dimensions and the level type.

Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement Learning is the closest form of learning to what humans would do. At its core there is an agent, who interacts with an environment and depending on its actions the agent gets positive or negative rewards. Rewards give the agent feedback for executed actions. The main goal of reinforcement learning is to maximize these rewards.

An example use case for this technique would be an autonomous car driving simulation. The car is the agent and the racetrack is the environment. The goal is to reach the finish line. As long as the car is on the track and driving, it gets positive rewards. If it moves off track it gets “negative rewards” (a punishment). At the start of a training session the agent has no knowledge of the environment or how to solve the given task. The learning process is split into two stages: exploration and exploitation. While exploring, the agent executes random actions and gets corresponding rewards. This is heavily used in the early phases of a training session. In contrast to that is the exploitation, in which the agent relies on what it has learnt before. The further the training process progresses, the more the agent will rely on exploitation. Different frameworks were considered for the learning process, whereby Deep Q-learning, DQN, and Double Deep Q-learning, DDQN, were available for selection in this project.

Both are based on the Q-learning algorithm and are further developments of this. Q-learning in its most basic implementation is a table with the number of cells corresponding to the number of states in the game. Each cell contains a value function for a corresponding state. Depending on the size of the problem and the number of variables, this table can take on extreme dimensions. One of several advantages of the selected frameworks over Q-learning is that the tables are dismissed and replaced with neural networks. These neural networks contain all information and are much less bloated compared to the tables. DQN is a group of algorithms that use a multi-layer neural network called Q-net, which outputs a list of action values for a given state. In contrast to DQN, DDQN uses two identical neural networks. One network is the current network that is updated during training. Whereas the second network is a copy of the current network from the last training iteration. The reason for this is to counteract against over-estimations of the action value, which can arise at DQN and lower the learning rate. For a learning process to take place, the weights in the neural networks must be updated. This is done with the help of an optimizer that tries to minimize a cost function.

Depending on the scale of the problem it might need several thousand or even millions of training iterations to achieve significant results. In the case of our pathfinding problem the agent is punished less for getting closer to the goal and heavily positively rewarded for reaching it. For every step it takes the agent is punished by a small amount. This punishment motivates the agent to not only find any path, but one that requires as few steps as possible. If the agent revisits known positions because it was crossing its own path or because it took a step back, it is punished as well. Trying to walk through walls or step outside the boundaries is heavily punished.

After successful training, the model is able to output actions for given conditions that lead to the pathfinding task being solved. To generalize the knowledge we also use transfer learning, which makes it possible for the agent to navigate in unknown worlds.

The Team

We started as machine learning amateurs who wanted to find out what machine learning can be used for and how it works. There was a lot to learn about the various machine learning concepts, the programming languages and frameworks involved.

Based on our preferences we split up into smaller groups, to simultaneously advance the different learning approaches. Paul worked on the training data generation and took the role as project manager. Mareike was more interested in generative adversarial networks. Daniel worked on data generation, visualizations and later joined Mareike. Steven chose to dive into reinforcement learning. Florian also worked on this and specialized further to look into transfer learning, so we could work with arbitrary inputs.

Even though everyone had their main focus, we frequently exchanged our knowledge and worked together to come up with improvements in our concepts, fix bugs and sort out technical difficulties.