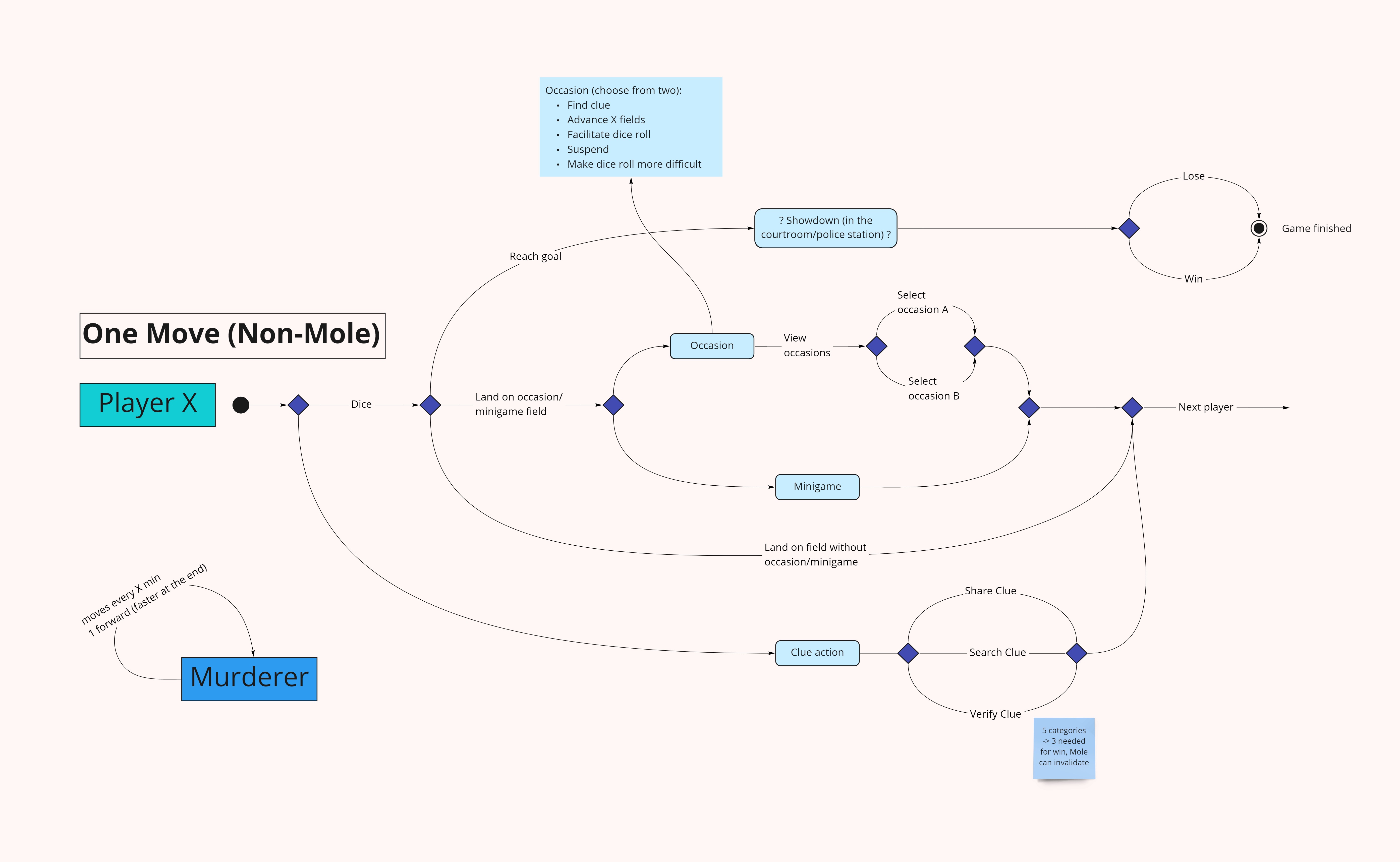

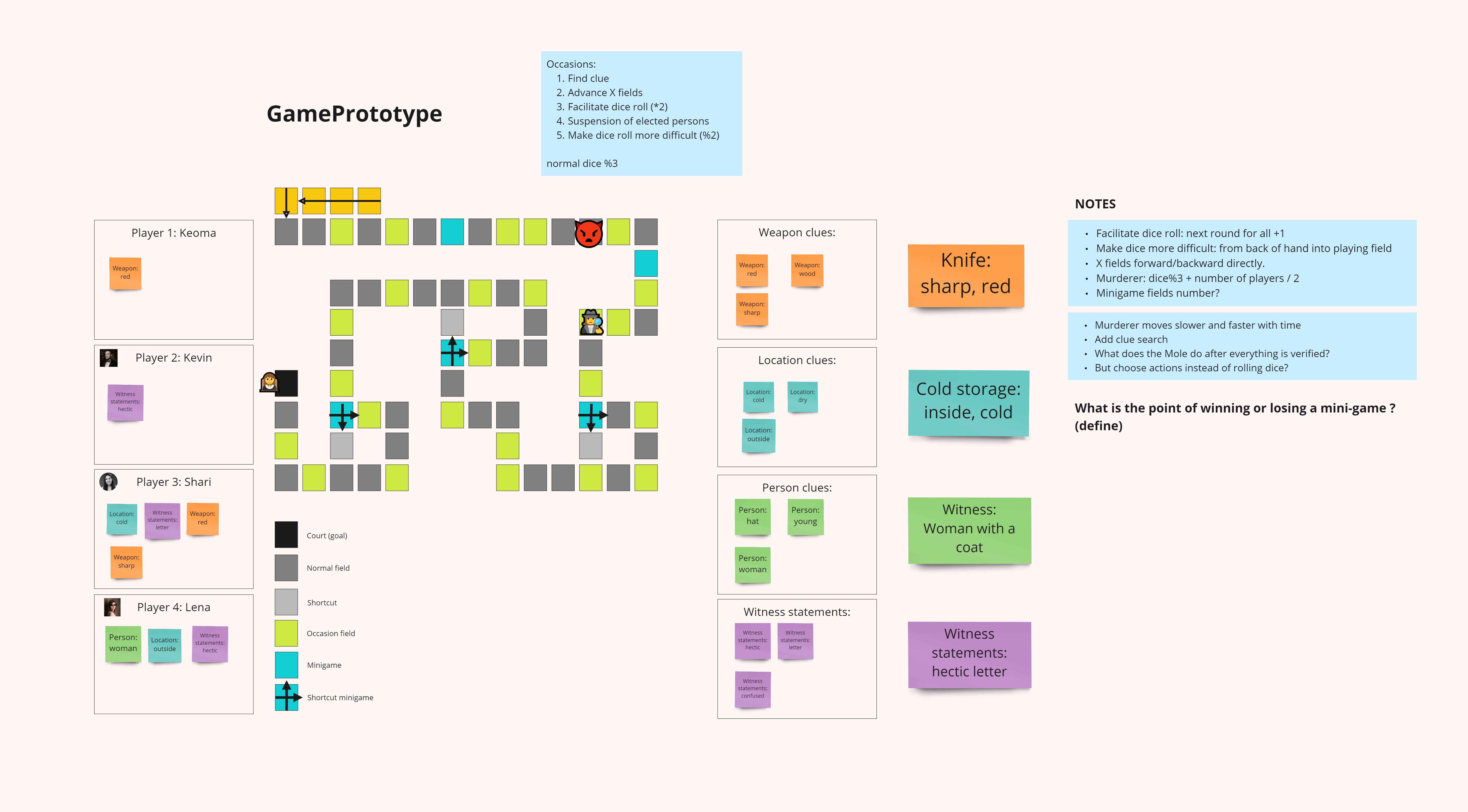

Our approach towards developing The Mole can be explained with the help of Schell’s Elemental Tetrad [1]. This is a framework for game designers to support them in creating a certain desired gaming experience while keeping the purpose and the dependencies between the four pillars mechanics, aesthetics, story and technology of a game in mind.

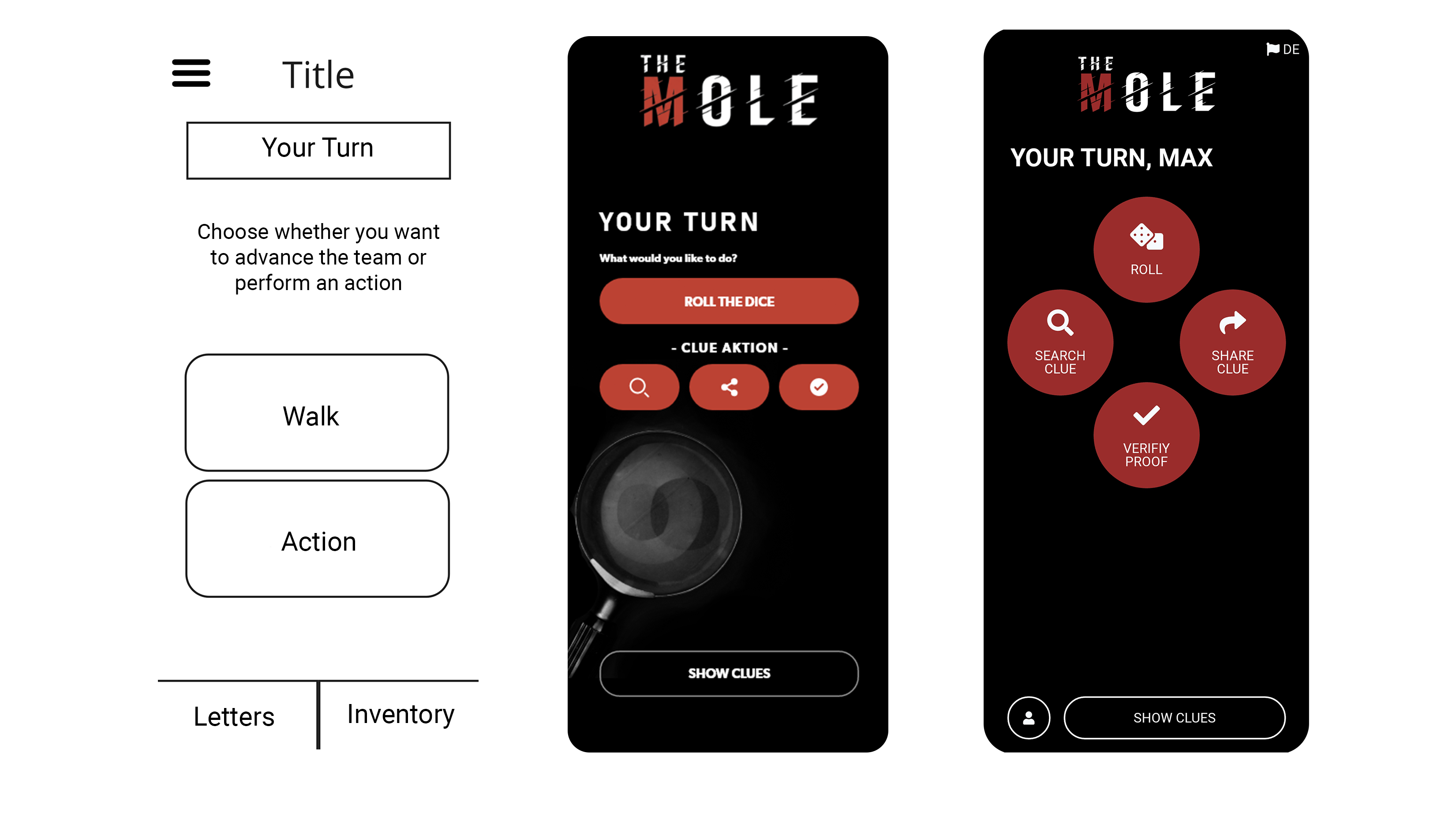

To predefine the gaming experience, we followed the given project guideline to create a board game augmented by digital elements. We further extended this vision to an exciting game for groups that would be fun to play remotely as well as in person. The game should thrill players by the central mechanism of unknown roles which they would have to identify and defend over the period of the game.

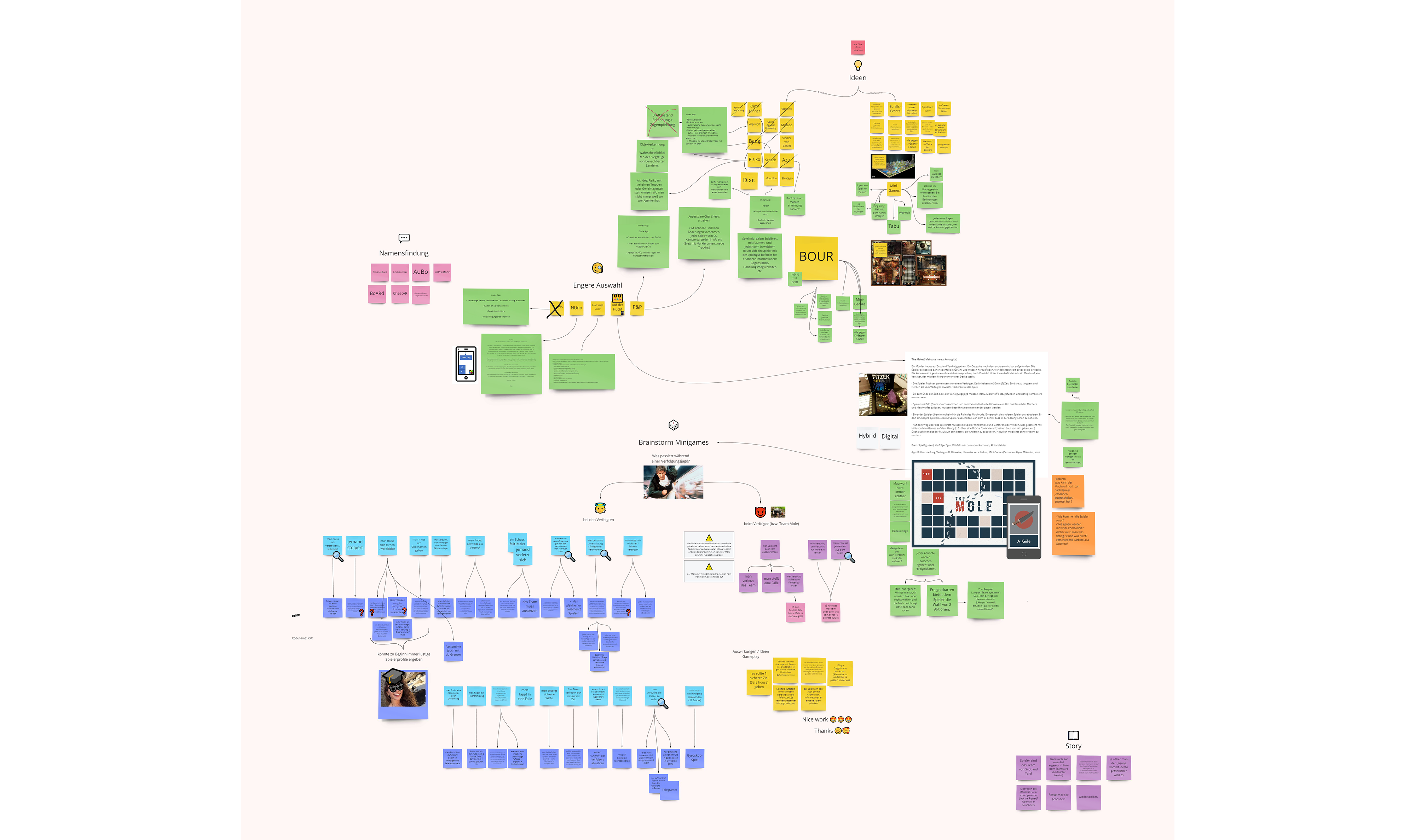

We started to work out the game idea based on further game principles which we knew from other games and enjoyed, and then came up with a few first graphical drafts. Thus, our process started with a focus on the game mechanics, slightly tending to the aesthetics.

Moreover, Bartle’s player taxonomy [2] can help describing our target group: The Mole players range between the “socializers”, those who mostly enjoy roleplay and interacting with fellow players, and the “killers”, those who enjoy damaging opponents and prefer competing with actual fellow players over artificial instances.